2. CHAPTER II.

The old man's home / 老人之家

1So wanderers, ever fond and true,

2Look homeward through the evening sky,

3Without a streak of heaven's soft blue,

4To aid affection's dreaming eye.

5CHRISTIAN YEAR.

6At the conclusion of the last chapter I gave the opinion that I formed of the old man from the brief conversation I myself had with him. The following incident cast, as it were, a shadow upon it, and robbed it of its brightness, but did not really alter it. My intercourse with him was brought to a sudden and painful conclusion. It was at my persuasion that he crossed a stile which separated the wild scenery of the landslip from the public road leading to the little village of B——. I thought it would be easier for him to walk along the more beaten track. He had yielded with apparent reluctance to my request. His unwillingness appeared to proceed from instinct rather than reason. It may in part have arisen from a kind of natural sympathy which attracted him to that wild luxuriant spot; in part from an unconscious dread of the danger to which he actually became exposed. He simply said, "This smooth way was not made for the like of me, kind sir; but under your protection I will venture along it."

7Alas! I little thought of the kind of protection he required. We had advanced but a few hundred yards, and had just reached the summit of the hill which commanded the first view of the village church. The old man had paused for a little while, and appeared to gaze upon it with a feeling of the most intense interest; I was afraid, even by a passing question, to interrupt the quiet current of his thoughts; when the silence was suddenly broken by the creaking of a cart-wheel, which grated harshly on my ear; and almost before I could look round, I heard a voice of rude triumph behind me, crying out, "There he is—there he is—there goes the old boy! Stop him, stop him, sir! he is mad."

8I have no heart to describe the scene that followed: the poor wanderer shuffled forward, with a nervous, hurried step; but in a few seconds the cart was at his side; the driver immediately jumped out, and, seizing him by the collar, with many a rude word and coarse jest, tried to force him to enter it. For a moment, surprise and indignation deprived me of speech, for I had began to regard the old man with such a feeling of reverent love, that it almost seemed to me like a profanation of holy ground. When, however, he turned his eyes towards me, with an imploring look, I recovered myself sufficiently to demand by what authority he dared thus molest an inoffensive traveller on his journey. In my inmost heart, I dreaded the answer I should probably receive; neither was my foreboding wrong; the man laughed rudely as he replied, "He has been mad, quite mad, for more than fifty years; he escaped this morning from the Asylum, and one of the keepers has been with me all day long scouring the country in search of him."

9It was in vain that I sought a pretext for disbelieving the truth of the story. I could not help feeling that it did but confirm a suspicion which, in spite of myself, had kept crossing my own mind; for the bright colouring which was shed by faith on the thoughts and words of the old man was not alone a sufficient evidence that they were under the guidance of reason. Yet, of one thing, at least, I felt sure, that, whatever were the state of his intellect, it could be no imaginary cause that now so strongly moved him. My heart bled for him, as I listened to the pathetic earnestness with which he implored the protection that I was unable to afford. He even forgot to use the language of metaphor in the agony of his grief. "Indeed, indeed, sir," he said, "they call me mad, but do not believe them, for I am not mad now. There, there," he added, pointing towards the church, "my wife and children are waiting for me. It was on this very day that they went away, and we have now been parted sixty years. I have travelled very far to join them once again before I die. Oh, have pity upon me! I only ask for one little half hour, that I may go on in peace to the end of my journey."

10Large drops of moisture trembled on his forehead as he uttered these words; his whole face became convulsed with emotion, and he clung with such intensity to my garment, that his rude assailant tried in vain to unloose his grasp. The man himself was evidently frightened by the agitation which his own violence had caused, and appeared doubtful how to proceed, when the scene was fortunately interrupted by the arrival of his companion.

11He was the keeper who had been sent from the Asylum with the cart, but had left it in order to search the pathway which led through the landslip. His look and manner afforded a striking contrast to those of the first comer, who proved to be merely the owner of the vehicle, which had been hired for the occasion. Immediately on his arrival, he reprimanded him for his rude treatment of the old man, and insisted on his returning to the cart, and desisting from all farther interference. My hopes were greatly raised by this, and I flattered myself that I should now have little difficulty in obtaining for the poor wanderer the indulgence which he sought. But I soon found my mistake; and, under the irritated feelings of the moment, almost preferred the rude conduct of the first comer to the quiet determination with which his companion listened to my request.

12He merely smiled at the account I gave of my own interview with the old man; and when I suggested that it contained no evidence of insanity, shook his head, and replied, "You do not know poor Robin. His notions about home are the peculiar feature of his madness; but you are not the first person that has been deceived by them."

13He spoke in a low tone, as though he were anxious not to be overheard. But the precaution seemed unnecessary; for, though the old man had mechanically retained his grasp on my garments, he was now looking eagerly towards the village church, and I could see, from the expression of his countenance, that his thoughts had passed away from the scene around him.

14When I found my arguments of no avail, I changed my ground, and besought as a favour that he would make the trial of letting the old man proceed to the end of his journey, and trust to his promise to return quietly from thence. "Sir," he replied, in a louder voice, "I should have no more hesitation in trusting the word of poor Robin than your own. He never deceived me; and, under ordinary circumstances, I would at once grant his request; but the hour is late, and, as it is, the night will close in upon us before we can get back to the town of N——. The responsibility will rest upon me, if mischief should arise from any additional delay. I am sure Robin himself would not desire it." As he said this, he turned towards the old man, but his countenance was unchanged, his eye still fixed upon the church, and he either had not heard the words at all, or they had failed to convey any distinct impression to his mind.

15After a pause, I again renewed my entreaties, urging that it would at least be a better plan than having recourse to violence, which must eventually produce a far more serious delay. "Of course," said the attendant, "anything is better than having recourse to violence." "Then," said I, "you accede to my request?" "Only," replied he, with a provoking smile, "in case all other methods fail; but as the delay would be a real inconvenience to us, you must permit me first to try my powers of persuasion. Let me now beg of you, whatever surprise you may feel, to be careful to express none." He again lowered his voice as he said these words, and, in spite of the dislike inspired by the self-confidence of his manner, and of other stronger emotions, my curiosity was excited to know how he would proceed. He placed himself opposite to the old man, so as to intercept his view of the village, and then, having fixed his eye calmly and stedfastly upon him, with an appearance of real interest, thus soothingly addressed him:—"I would gladly go on with you, Robin; but am sure you are under some mistake. Your wife and children cannot be in yonder village,—they are not there, they are at home. Come quietly with me now, and perhaps this evening you may go home also."

16These simple words touched some hidden chord in the old man's heart, and their effect was almost magical. All other feelings passed away, and I forgot the presence of his companions, as I watched the change which they produced. His features became composed, his hand relaxed its hold, and his voice resumed its former tranquil tone, as he slowly repeated: "They are not there, they are at home; they are not there, they are at home. True, very true, they are not there, they are at home."

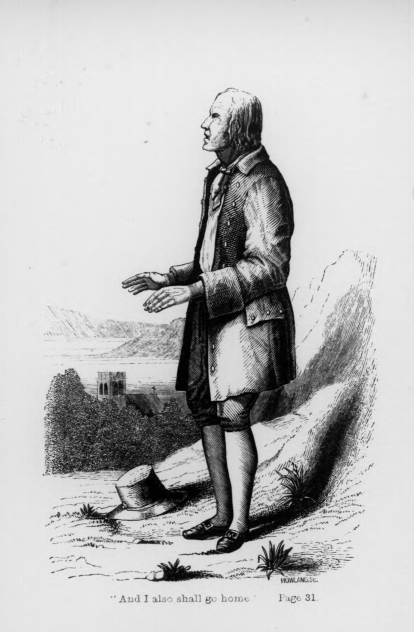

17Presently he raised his eyes to Heaven, and the attendants, no less than myself, were overawed by the solemnity of his manner. There was a silence of a few seconds, during which he seemed to listen intently; and then, as though he had heard some echo from above, which confirmed the hope that had been held out to him, he confidently added: "And I also shall go home,—and this very evening I shall be there."

18While I was still pondering on these words, the old man had of his own accord quietly placed himself in the cart, and his companions had seated themselves by his side. They were on the point of driving off before the thought occurred to me of offering him money. I drew out my purse, half expecting him to refuse the proffered gift; and it was with a strong feeling of disappointment that I observed the look of satisfaction, almost amounting to eagerness, with which he took the silver from my hand. I said within myself, "Can it be, then, that the taint of covetousness is to be found in a mind from which every earthly affection seems so entirely to have been withdrawn?" But I wronged him by the thought. The money was immediately taken from him, and he resigned it to another no less gladly than he had received it from me. "It will not do," said the keeper, "to let him have it himself: he will merely give it away to the first beggar that he meets. He has not the slightest notion of the real value of money. It shall be laid out for his benefit; and till then it will be safe in my keeping."

19My countenance may have expressed dissatisfaction at the change, though, in truth, I had no objection to make to it. But the old man himself interrupted me before I could reply, and said, "Do not be afraid, kind sir, whether it remain with me or him; your treasure will be safe, quite safe; it matters not now whether it remain with me or him;" and then added, in a more solemn tone, "safe 'where neither rust nor moth doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through and steal.' I will take it home with me; and when you also go home, you will find it there." And I now understood how it was for my sake that he had so gladly welcomed the gift; and I thought, too, that if in truth money had a real value at all, it must be the one which was assigned to it by him.

20The men were in a hurry to depart, and I was now forced to bid adieu to the old man. He appeared so sorry to leave me, that I promised on the morrow to come and see him. I did not like to use the word Asylum, so I said at his dwelling-place. The expression at once caught his ear, and re-awakened the train of thought which my gift had interrupted for a time.

21"Not in my dwelling-place," he said, "for to-morrow I shall not be there. If you see me again, kind stranger, it must be at home. May God bless you, and guide you on your way." The cart was already in motion, but he looked back once more, and waved his hand as he said, "Good bye, sir. Remember that we all are going home!"

22They were the last words I heard him speak, and it is perhaps from that cause that they made so strong an impression on my mind; for often since then, when I have been tempted to wander from the right path, or murmur as I walked along it, I have thought upon the old man's parting warning, and asked myself the question, "Am I not going home?"